By Yashi Banymadhub

When I saw Kier Starmer announcing his “biggest trade mission to India”, my thoughts went not to economics but to my great-grandma. Her stories of life under British occupation in Mauritius opened my eyes to how Britain used brown bodies for profit.

Why the leap from trade deal to empire? I’m not alone in the mental gymnastics. Other Indians described it as the “East India Company loot 2.0” and warned “a similar crowd came centuries ago”. In an Instagram reel, Starmer is seen addressing passengers from the cockpit of his British Airways flight from Heathrow to Mumbai.

Cultural theorist Nicholas Mirzoeff calls visuality ‘the right to define what counts as the visible world — the right to be the point from which the world is seen. In Starmer’s video Britain once again occupies that vantage point, the pilot’s seat, which carries colonial undertones.

That same hierarchy — who gets to move, who must move and who controls the narrative — persists in today’s politics of trade and migration. So when Starmer proudly declared to be leading the biggest trade mission worth £6 billion, Indians didn’t hear “partnership” but an echo from the past.

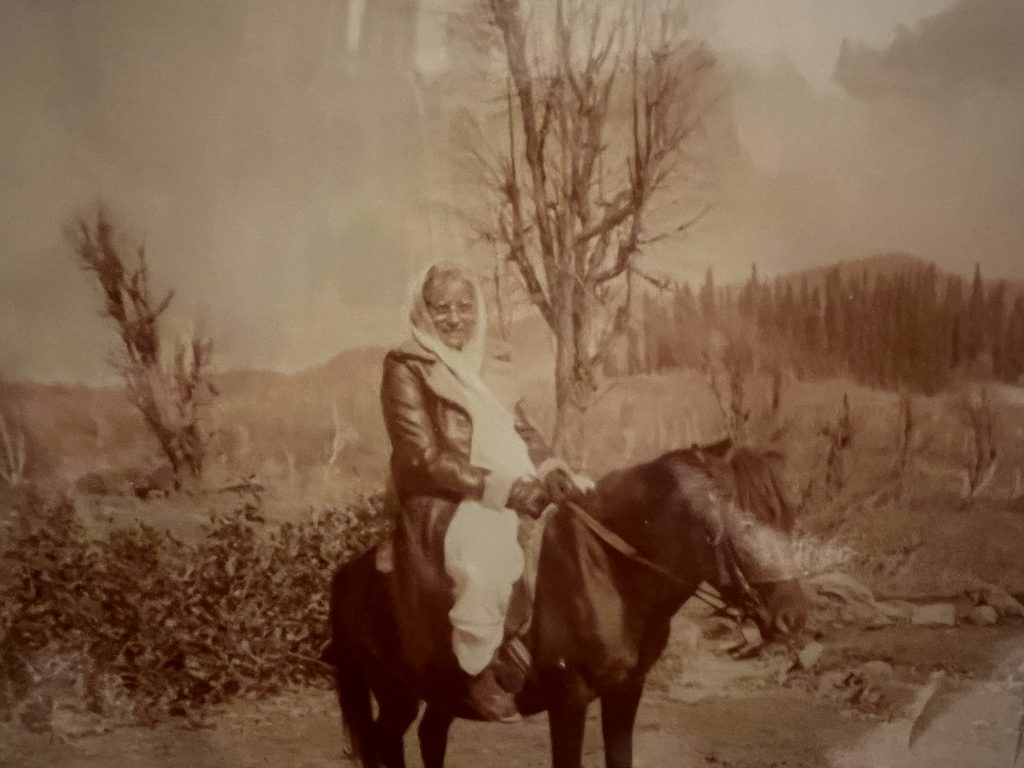

The British Empire replaced slavery with indentured labour in 1834 and that is how I ended up as a French-speaking Indian living in Africa. When my great-grandparents left India in the 19th century they were sold it as a job opportunity. It was in reality another form of bonded labour. My great-grandma — who I lived next door to growing up in Mauritius — spoke of frightening encounters with British colonisers. If she saw them approaching, she would hurriedly take off and hide her shoes, as there was a tacit rule that footwear was only for the whites. Not following it could result in a beating. Walking miles to the only school that admitted non-white pupils, not to educate them but to instil obedience, was deemed too dangerous and her attempts at getting an education were cut short. She learned to write before visiting her grandson in India, insisting on a proper signature on her passport instead of an undignified thumbprint.

When I knew her, she wore white sarees exclusively. This widow’s attire added a softness to her, especially when she sat engrossed in the Ramayana muttering softly under her breath, or when she poured water from a copper pot (lota) greeting the rising sun at dawn each day. But as a woman and single mother, she was a force to be reckoned with, witty and, if crossed, foul-mouthed. She would sit in front of my blackboard patiently while I taught her the new English words I’d been learning at nursery: “woman”, “man”, “girl”, “boy”. The last difficult-to-pronounce one would result in a telling off from me and a strike, interrupted by my mum, with the ruler I held menacingly in my hand. (No, I do not condone corporal punishment in schools but some have made links between how children in the Global South are disciplined to how people were treated by colonisers, and the passing down of trauma through the generations.)

As Sathnam Sanghera notes in Empireworld, the British took over Mauritius from the French in 1810 and kept running it as a slave colony long after abolishing the slave trade. He draws a crucial distinction: Africans were enslaved — owned, dehumanised, treated as property — while Indians under indenture endured a different, but still brutal, “semi-slavery.”

His words echo my family history. My ancestors were imported labour; today’s migrants are disposable labour. The UK-India trade deal follows Starmer’s pledge to cut over-reliance on migrant labour, proving that Britain loves Indian money but not Indian people. Immigrants are used as scapegoats by politicians seeking to stir up racial hostility, despite the fact that they contribute more in taxes than they claim in benefits.

When we talk about trade without talking about immigration, we forget that British wealth was built on the movement of people — who were often unwilling, exploited and stripped of their humanity — as well as goods.

It’s time that Britain comes down to earth instead of forever looking down, from the cockpit, on others.